Lately, one of the key subjects I’ve been studying and thinking about is Quality for Machine Learning Systems. I remember a couple of years ago when entering the field of ML that I had no idea how to measure quality. By that time, I was writing my first unit tests for web servers and had the first initial view on what quality is for Software in general, but when it came to ML, I had no idea what to look out for.

In this series of articles, I will try to introduce a little bit about Quality for ML Systems, specifically testing, monitoring, and some tips on situations you will probably encounter in the industry.

We will start the series with a better view of ML Systems and the challenges we have when dealing with quality.

About ML Systems

What is an ML System

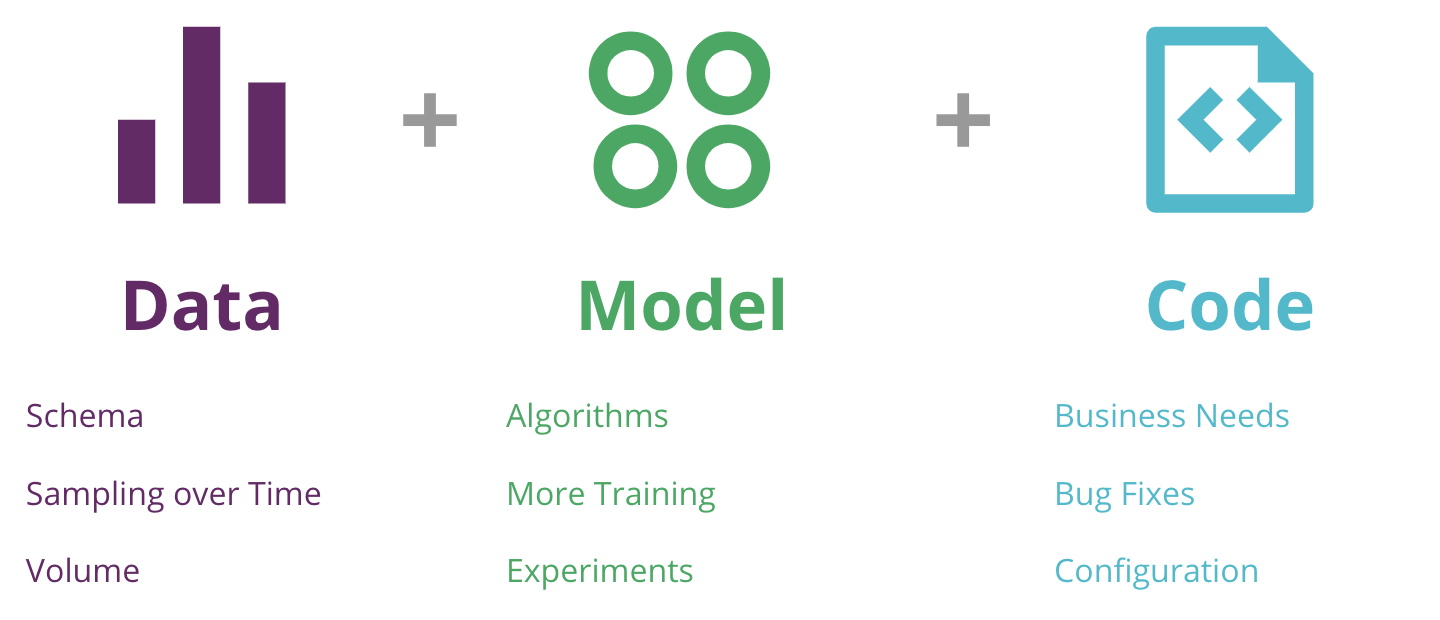

Before starting, it is nice to have a better understanding of what an ML System is as this will give us a better understanding of the challenges we have for Quality. ML Systems/Applications are very different from traditional systems/applications because they have an extra axis of change or complexity; a very nice view of this is given by Sato, Wider, and Windheuser (2019) in the CD4ML article:

The authors provided not only the decomposition of the System/Application for their axis of change but also some examples of the changes:

- Data: this is the fundamental difference for ML Systems, the expected behavior is not given by the application, but by the data. The examples are evolving schemas, volume, and different samplings over time.

- Model: here we have the foundation for learning from data, different statistical techniques, and algorithms that allow us to make new predictions. Some examples of changes are different algorithms, multiple experiments, and longer training periods.

- Code: the commonplace in comparison to traditional applications where have code for configuring models, different serving scenarios, etc. There may be some changes depending on business needs, bug fixes, and different configurations.

The ML Lifecycle

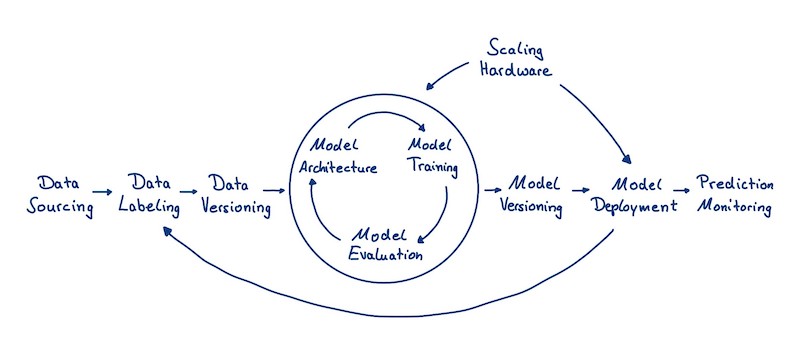

If you have a minimal background on ML, you probably are familiar with the Machine Learning Lifecycle:

We basically have three main stages:

- Data Collection: IMO, these are the most important steps on the lifecycle (remember the ML scenario: “Garbage In, Garbage Out”). You could also add the Feature Engineering step on the diagram above to have a better view of this stage. In the industry, these steps are usually performed by the Data Engineer.

- Model Training: these steps relate to building the model, evaluating it, and training it. You could probably add the EDA step outside the model optimizations circle to have a better view. Here we have the role of the Data Scientist that has a good understanding of the data, the business, and also on the ML techniques to be used.

- Model Deployment: finally, we have steps related to deploying the model in the production environment, for making real predictions. These steps are usually performed by the Machine Learning Engineer, although you will find many places where the Data Engineer is also responsible for deploying the model. You can see that there are some situations where the predictions made by the model actually affect the data that will be used for the next versions of the model or new models.

The Challenges for Quality

I’ve introduced two general concepts that are the composition (or the moving parts) and the lifecycle of the ML System and by now you’re probably suspicious on what are some challenges in this scenario.

Moving Parts & Different Teams

We’ve seen that ML Systems have three different axes of complexity and they don’t evolve at the same time or velocity, not only that but also different teams work on different steps of the ML lifecycle. That means that keeping an eye for changes is very hard and almost impossible if you have multiple models and teams working in the same organization; a very chaotic environment, indeed.

To illustrate I will give two brief examples (that could be related to real situations or not):

“Organization ABC has just deployed its first ML Model to increase sales, consisting of an API. As they had very little previous experience with the theme, they hired a Data Engineer and a Data Scientist, who worked hard to deploy this model. They start to iterate for new models but due to a bug they need to rollback to the previous version, little did they know they forgot to implement model versioning.”

“Organization XYZ is mature on Data Science and has different Machine Learning Models on production, it also has a team dedicated for building data pipelines and feature serving, another team for building a Machine Learning Platform to train models and to deliver an experimentation environment for Data Scientists. Unfortunately, one day, after deploying a new model the business team finds out that there is something really wrong with a particular ML System, and tries to find out what is wrong with it, little did they know that information was scattered around between multiple applications, versions, authors, etc… Who is to blame?”

Data-driven Process

Another thing to notice is that testing data-driven applications are hard. We will talk a little bit more about testing and quality, but generally speaking, it is easy setting expectations for traditional applications because the behavior is written on the code, but how about ML Systems, where the behavior is on the data?

You could argue that it is easy as separating a slice of the test set and setting expectations on that slice, but can we be sure that only doing that we are asserting model quality? Or maybe some instances are harder to classify than others? What about edge cases or key cases?

Because we are dealing with a data-driven process, ensuring quality for a model is very hard; in a scenario where we want to also be able to deal with ML Ethics (Ethical AI), it is very important to ensure expectations on different data categories/slices. Using a simple metric for that may not capture all different predictions and distributions.

Another very important thing to keep in mind is that unexpected inputs will be received by your application at some point. Yeah, because we are dealing with lots of integrations, there will come a time where your model will receive a negative number for age, or a category that does not exist, etc.; if you are not able to ‘sanitize’ your input you can get into a very bad situation, especially if your model feedback to your data pipeline, and you can also risk on making the wrong decisions (predictions).

Take a look at this example:

“Organization PQR uses ML for some considerable time for performing fraud prevention. Nevertheless, when trying to interpret the mode, the Data Scientists began to notice that one particular feature has a really counterintuitive meaning, and also the performance for the model, across different versions, began to degrade 9 months ago. Until they found out that one of the features given to the model had a bug and was providing unexpected values for some cases.”

Lots of configuration

Finally, I would like to talk a little bit about configuration issues. As we saw above, in the diagram by Sato, Wider, and Windheuser (2019), a lot of configuration resides inside code files that are stored on your VCS (note that keeping configuration on databases is not really a good practice because it introduces errors and makes it really hard to keep track). These files probably store lots of configuration: about your model (for training or scoring), about the data, and also about how the model is trained (hyperparameters).

You can think that this is a very trivial and useless subject, but keeping an eye for quality on configuration files is really important and can be very complex depending on how the configuration file is processed. Also, a simple change on a parameter may pass unnoticed until you see a hole in your system.

One example to serve as a guide:

“In organization XYZ a Data Scientist developed a new version for a particular batch model. The organization maintains a second environment for integration and full end-to-end tests where the models are deployed before production, but the specifications for the environments are different. After passing all tests the model is deployed and fails for all executions, the Data Scientist tries to debug the execution of the model using the previous environment but everything seems to work fine. After involving multiple teams to look for the problem in the production environment they found that one of the parameters on the configuration file still points to the backtesting environment.”

Wrap Up

In this article, I tried to introduce a little bit about why it is important to keep an eye for quality for ML Systems and some challenges. We’ve seen some of the points on different degrees of freedom for the ML System and also that different teams and actors are responsible for specific tasks on the Machine Learning Lifecycle.

For the next article, we will try to look into testing and four different categories where testing is appreciated for ML Systems; the examples and points I raised here are based on experience and also on a very nice list of resources you will find below.

References

RUBAN, T. The Deep Learning Toolset — An Overview. 2018. Available at: https://medium.com/luminovo/the-deep-learning-toolset-an-overview-b71756016c06

SATO, D. WIDER, A. WINDHEUSER, C. Continuous Delivery for Machine Learning. 2019. Available at: https://martinfowler.com/articles/cd4ml.html

BLASZKA, D. Dangerous Feedback Loops in ML. 2019. Available at: https://towardsdatascience.com/dangerous-feedback-loops-in-ml-e9394f2e8f43

SCULLEY, D. HOLD, G. GOLOVIN, D. DAVYDOV, E. PHILLIPS, T. Hidden Technical Debt in Machine Learning Systems. 2015. Available at: https://papers.nips.cc/paper/5656-hidden-technical-debt-in-machine-learning-systems.pdf

BRECK, E. CAI, S. NIELSEN, E. SALIB, M. SCULLEY, D. The ML Test Score: A Rubric for ML Production Readiness and Technical Debt Reduction. 2017. Available at: https://research.google/pubs/pub46555/